‘The range of what we think and do is limited by what we fail to notice……’

R.D. Laing

How many of us, when undertaking risk assessment, sometimes fail to see ‘the wood for the trees’?

How many of us, when undertaking risk assessment, sometimes fail to see ‘the wood for the trees’?

With any job, becoming entangled in wider workplace issues may end up blurring our focus on the tasks at hand. An adequate response to a manual handling risk may be just ‘under our nose’, but in a forest of competing concerns, do we always notice the blindingly obvious?

Of course, we can also fail to see ‘the trees for the wood’. Our focus on the job or on the employee undertaking the tasks may exclude the wider context e.g. tasks ‘up-stream’ or ‘down-stream’ from the job itself that may be impacted by any change we hope to implement.

So where to start? With the parts or the whole? With the wood or with the trees?

When it comes to an ergonomic approach the distinction is of course artificial. An ergonomic view will include both breadth and focus. We notice what is in front of us and we notice what is around us and we notice how the two interact. The ability to see what is going on and ask the right questions is of course a key skill for any risk assessor. Are the hazards obvious? Who may be harmed? How might they be harmed? What questions do we need to ask to determine the levels of risk involved? What are we going to do about it?

The Manual Handling Operations Regulations (L23) give us a simple template which helps focus our observations and enquiries regarding manual handling hazard (see Schedule and Appendix 1). The guidance provides a framework for assessing, and by implication managing, manual handling risks in the workplace.

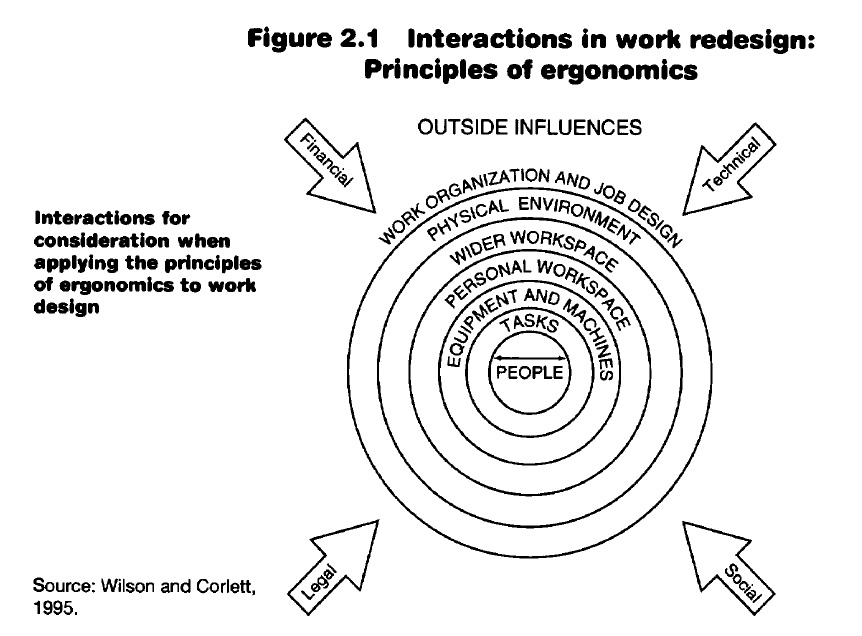

Our powers of observation and enquiry may also benefit however from knowledge of, what some have called, ‘The Ergonomic Onion’ – a model used in ergonomic task analysis or job design.

The people that do the job are at the heart of ‘the onion’.

Right at the heart of the ‘onion’ is, of course, the people that do the job. What personal characteristics (age, gender, etc.) may be important to consider? What about their physical abilities, their health, their training, etc?

Broadening our observation and enquiry out will lead to a consideration of the tasks undertaken. Does the job involve inefficient postures, repetitive work, heavy lifting, etc? Is the use of equipment and machinery relevant? What do we notice with respect to the interaction between the people and the equipment? How does it affect their performance and well-being?

Of course, all of this takes place in a working environment. What do we notice about their personal workspace and/or their wider workspace? Does the design of their personal workspace, for example, impact on how well the tasks are performed; or in the wider workspace, does access or egress pose a problem?

We may also need to consider the physical environment e.g. lighting, temperature, noise, dust, etc. Widening out our vision even further we may consider aspects of the work organisation and job design e.g. job rotation, job enlargement, team working, psychosocial issues, etc. or even ‘outside factors, such as financial, technical, legal or social.

Being a dynamic model the various layers of the ‘onion’ will, of course, overlap and interact with each other. We see both the wood in relation to the trees, the parts in relation to the whole. By ‘noticing’ these inter-relating factors and by implementing change we hopefully provide jobs that are not only less hazardous but also satisfying, productive and complementary to the rest of the organisation’s activities.